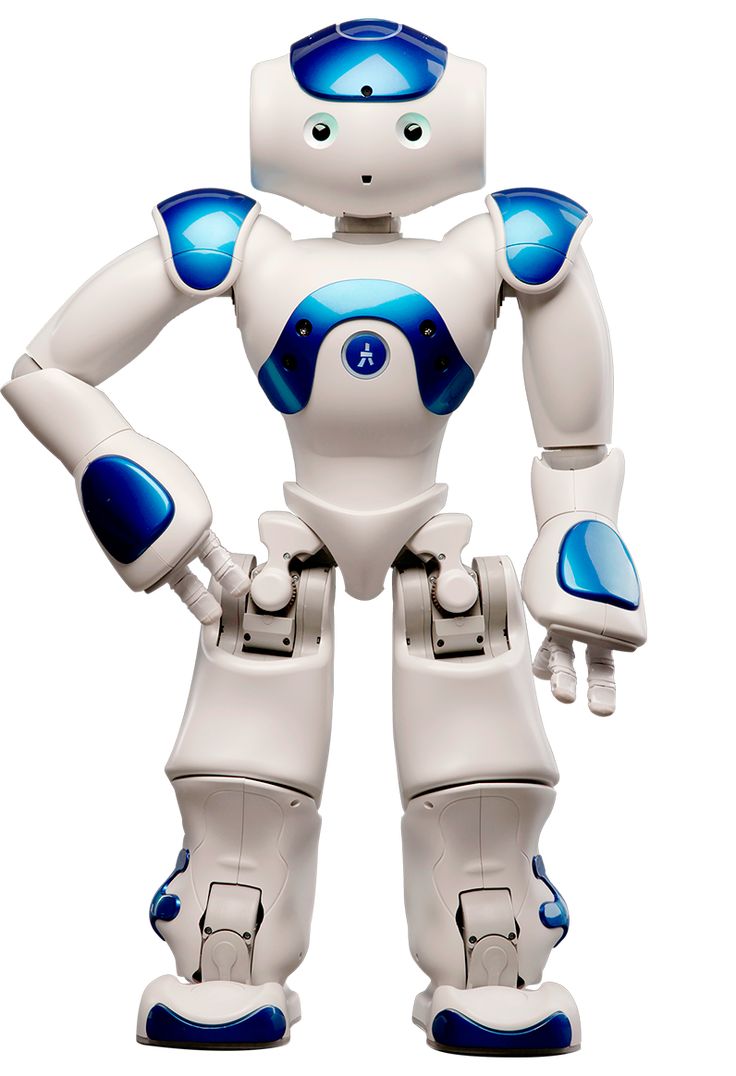

Maximo automated solar panel installation, leveraging the quality and precision of an industrial robot mounted on a mobile chassis. | Credit AES

While some are wondering if robots will take away jobs, AES has given them the dirtiest and most boring job — literally. Under the scorching sun of California, the fourth generation of robots named Maximo methodically installs giant solar panels, doing in a day what a team of people would take a week to do. And all this with a grace worthy of an industrial ballet.

Solar Farms: Before and after robot movers

Imagine: a desert, forty degrees of heat, and a team of exhausted workers turning 300 panels a day. Each one is the size of a good suitcase, about 80 pounds (36 kg). Chris Shelton, technical director of AES, describes this process without unnecessary romance.: "This is a highly repetitive job. Just take it out of the box and attach it to the pipe." It is precisely this kind of routine that the Maximo robotic service is designed to eliminate.

AES, one of the giants in the energy industry, relies not just on robots, but on a whole technological service. They don't sell hardware, but charge money for the installed module. "We are entering the market with a complete solution, not just technology. We believe this is the right approach for our industry," says Shelton. In fact, they rent out robots along with their "brains" and "eyes".

What can this mechanical brigade do?

Maximo is based on an industrial six—axis manipulator mounted on a mobile platform. His smaller brother is sitting next to him, whose task is to get under the panel and complete the fastening. The platform is not yet autonomous and modestly follows the tractor, but AES engineers are already dreaming of completely independent movement.

The key bet was placed on two technologies:

AI vision: The system must recognize panels of different manufacturers and sizes in any light, from blinding noon to cloudy weather.

Industrial robots: They took proven, reliable manipulators, stuffed them into dust- and moisture-proof cases and sent them to the desert.

The result? Four of these robots churn out 1 megawatt of power per day, which is about 1,900 panels. They are already hard at work on the Bellefield project in California, the largest solar battery complex for Amazon in the United States, building about 15% of its second stage.

Aren't people needed now?

Don't rush to write off humanity. Maximo robots are not soulless invaders, but rather ideal performers for tasks that are simply dangerous and tedious to humans. They don't complain about the heat, don't require sunstroke insurance, and don't get tired by lunchtime. They are "hired" through engineering and construction companies (EPCs) that build farms for AES and other players.

Speaking of hiring. While some robots are working on construction sites, others are looking for a use for themselves. There are even entire ecosystems, like jobtorob.com where highly skilled machines can find a suitable "project". Even a robot should have a career, right?

Big batteries for big brother

The irony of the situation is that robots building solar farms indirectly feed the insatiable thirst for energy on the part of... other robots. More precisely, artificial intelligence and data centers. The very Bellefield complex that helps build Maximo consists of half of giant batteries. And all this power will be used to ensure the operation of Amazon cloud servers.

"That's 1,000 megawatts of solar power and 1,000 megawatts of batteries," Shelton says. It turns out to be a kind of "green" vicious circle: robots build farms that feed AI, which, in turn, teaches new robots. Poetry of the technological era.

What's next? A future where grass doesn't grow

By the second quarter of next year, AES plans to launch the fourth generation of Maximo. The ambitions extend beyond a simple installation — the company is working on an intelligent planning platform that will optimize the entire logistics of construction. Soon, robots will not only fix the panels, but also decide in what order to do it more efficiently.

One philosophical question remains. When all the solar farms on the planet are built by tireless mechanical workers, where will these robots themselves go? Maybe they'll be sent to the nearest empty planet to start all over again? Or will they finally make up a resume and go looking for a new job on specialized platforms? The future will show. In the meantime, they're just doing their job—faster, more accurate, and without a single complaint about the weather.