*More than one approach to the ‘electric stack’ is possible for battery technology to advance. Source: Adobe Stock

We live in an era when robots do somersaults, drones deliver pizzas, and electric cars accelerate to hundreds in three seconds. But all these technological wonders are united by one humiliating detail: somewhere in the corner of the room, a wire stretches to an outlet, like an umbilical cord connecting a fantastic future with a mundane present. While scientists are promising batteries with exorbitant capacity, the real revolution is stuck in the most unexpected place — on the assembly line.

What's wrong? There is science, there is no production

Laboratories around the world annually patent hundreds of breakthrough technologies: solid-state batteries, silicon anodes, and aluminum-air cells. But there is a gap between the laboratory sample and the mass-produced product, which is filled with unresolved engineering problems.

"The problem is not that we don't know how to create a better battery. The problem is how to create it by the millions, while maintaining stable quality and low cost," explains a leading researcher in the field of energy storage.

Major production bottlenecks resemble traps for innovation:

The curse of the vacuum. Many promising technologies require assembly in ultra-clean rooms or in vacuum chambers. Scaling up such production is like trying to build a spaceship in an ordinary car factory.

The calibration paradox. Modern batteries require jewelry precision when applying active materials. A difference in the thickness of the layer of several microns can reduce the cell capacity by 20%. Imagine that you need to spread butter evenly on a kilometer-long toast with an accuracy of a millimeter.

The drying dilemma. The production of lithium-ion batteries involves drying processes that take up to 48 hours. It's like baking pies in an oven that only works in one mode — "very slow".

Why is this not just about your smartphone?

Delays in battery development are holding back the development of entire industries:

Robotics. The autonomy of industrial robots is limited to 4-8 hours, after which they need to be recharged.

Green energy. Storage devices for solar and wind power plants remain too expensive

Aviation. Electric planes can only fly for short distances.

Medicine. Implantable devices require frequent battery replacement

"Every additional hour of the robot's battery life means 15% less downtime and 20% more productivity," the logisticians calculate.

Who is to blame and what to do? Recipes from practitioners

Solving the problem requires a systematic approach, not individual breakthroughs.:

Automation of quality control

Modern factories are starting to introduce robots with computer vision that check each battery cell for microscopic defects. This reduces the rejection rate from 5% to less than 1%.

Modular production lines

Instead of creating giant factories for a single technology, companies are developing modular lines that can be quickly reconfigured to new element formats.

AI for process optimization

Machine learning helps predict optimal production parameters, reducing the time for experiments. Algorithms analyze thousands of variables, from air humidity to coating speed.

Energy Park Management of the future

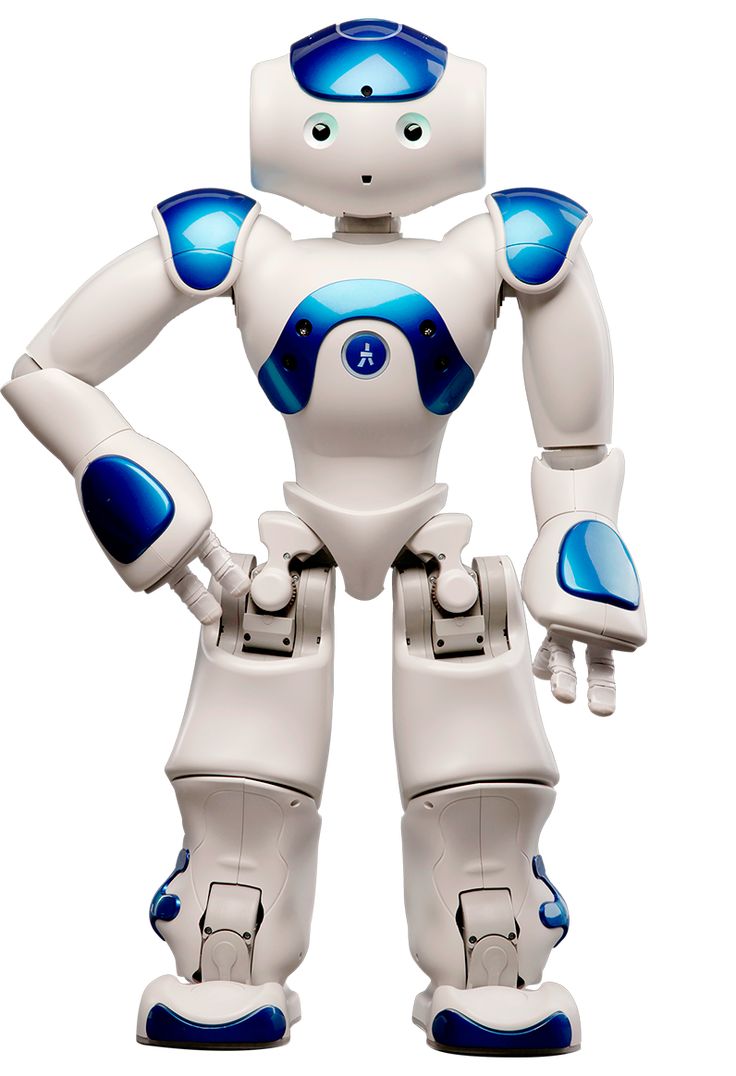

As thousands of heterogeneous devices with different power requirements appear in industry and everyday life, a new task arises — the management of this "energy economy". How can charging capacities be optimally distributed among the entire fleet of robots in the warehouse? How do I plan their work shifts based on the charging time?

Specialized management platforms may be required for such tasks. For example, the logic of an ecosystem jobtorob.com , which positions itself as the world's first robot hiring platform, can be expanded to manage their "energy profiles." The system could automatically distribute tasks between robots based on their charge level, prioritize access to charging stations for mission-critical tasks, and even "hire" additional robots from outside during peak loads when its own fleet is low.

What's the bottom line? The future is still plugged in

While marketers are painting pictures of the wireless world, the reality is that we will remain connected to power outlets for the next 5-7 years. But there is also good news: the main investments in the battery industry are now directed not to scientific research, but to the development of production technologies.

"We are on the threshold of the second stage of the battery revolution," analysts predict. "If the first stage was about discovering new materials, the second stage will be about how to produce them efficiently."

The speed of our transition to a truly wireless future depends not on brilliant scientists in laboratories, but on engineers on production lines who solve prosaic but mission-critical tasks. And, perhaps, soon the resume of a successful robot will include not only "50 kg load capacity", but also "95th percentile energy efficiency" with recommendations from the energy management system.