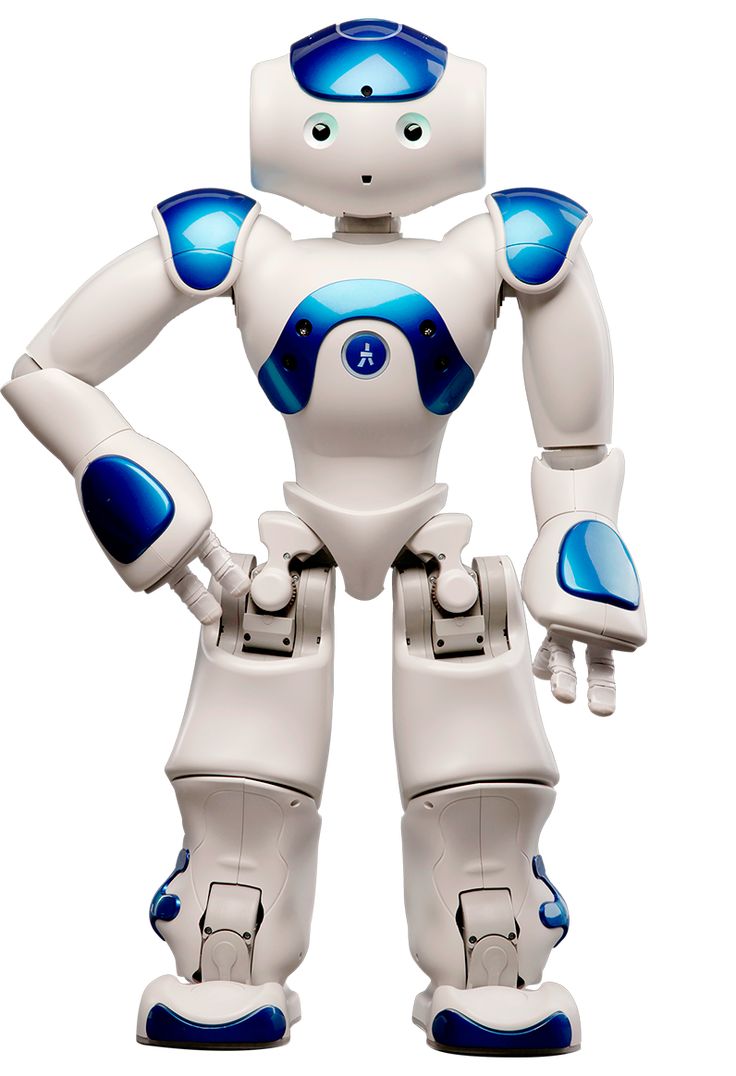

Sharks possess electroreceptors that make them sensitive to electric fields. This can be used to protect humans.

Source image: Adrian Weston/Alamy

Encountering a shark in open water is a nightmare familiar to anyone who has seen Jaws. But what if the predator's main tool can be turned against itself? Australian engineers from Griffith University have found a way to turn sharks' unique superpower—electroreception — into their main weakness. Their research, published at the end of 2025 in IEEE Sensors Letters, paves the way for the creation of wearable devices that will create an invisible electric shield around the swimmer without harm to humans or marine life.

Shark's Superpower: How "Natural antennas" work

The key to technology lies in understanding biology. Sharks, rays, and some other fish have a unique sensory organ called electroreception. There are hundreds of Lorenzini ampoule pores on their muzzles, capable of detecting the negligibly weak electric fields generated by any living being when muscles move or the heart beats. For a predator, this is a navigation system and a prey detector operating from a distance.

The engineering idea is simple and elegant: if you create a controlled but stronger electric field, you can not mask a person, but, on the contrary, "scream" at the frequency of the shark's sensors, causing her discomfort and a desire to swim away. Studies have shown that the threshold required for scaring varies depending on the species: from a modest 3 V/m for bull sharks to 18.5 V/m for hammerheads. It is important that these levels are within the limits of safe norms for humans and do not harm the shark itself — they only create unpleasant sensory noise.

The main enemy is water: why is it so difficult to create an electric shield

The main technical problem is not in the generation of the field, but in its range. Seawater is an excellent conductor. The electric current in it dissipates at an incredible rate, which leads to a sharp drop in field strength with distance. This is exactly the problem that the team led by Professor David Thiel and Hugo Espinosa studied.

They tested a compact generator of pulsed fields (5000 V, 8.5 kHz) in water with different salinities: from fresh to ocean. The result was predictable: the field was fading really fast. However, the key discovery was that the nature of the field was similar in different environments. This means that by solving the range problem once, it will be possible to create a universal device that works both at the mouth of the river and in the open ocean.

From wristband to smart beach: the evolution of the security concept

Today, the team is focused on optimizing the wearable device: finding a balance between power, electrode size, pulse design, and battery life. "For wearable systems, these limitations are quite significant," says Professor Thiel. However, their vision extends much further than an individual gadget.

The next stage is the creation of a distributed security system. The researchers propose to deploy a network of underwater field generators on popular beaches. Although the range of each device is small, a properly positioned and synchronized network can create a continuous protective zone. "A distributed array can form a large protective zone if the distance between devices, their overlap and power consumption are properly optimized," explains Espinosa. This transforms the technology from personal to infrastructural, where each element of the network performs its own narrow task, and their well-coordinated work ensures overall security. Managing such autonomous network systems is a challenge for future intelligent platforms that could coordinate the "operation" of distributed devices, similar to the concept of JOBTOROB.com explores the logistics of tasks for swarms of robots.

This approach radically changes the paradigm of protection from sharks. Instead of passive networks, which often harm the entire marine ecosystem, or individual means with questionable effectiveness, we get a smart, targeted and humane system. It does not harm animals, does not pollute the water, and only works when needed. Perhaps in the future, shark scaring will become as standard and inconspicuous an urban service as street lighting.

An ethical breakthrough: safety for all

The development of Australian scientists is important not only for its engineering component. This is an example of how technology can resolve conflicts between humans and wildlife without harming the latter. The device doesn't maim or kill sharks — it just "speaks" to them in their language, politely asking them to stay away. In an era when many shark species are under threat of extinction, such a humane approach is the only right way.

A technology born out of a desire to understand nature, rather than conquer it, can become the gold standard for coexistence in the ocean. And then swimming in the sea will no longer be a roulette game based on irrational fear, but will turn into a relaxing holiday protected by an invisible but smart shield.