The Moon Surgical Maestro robotic surgery system faces some stiff competition — and the device developer plans to use that to its advantage.

In an interview with Medical Design & Outsourcing, Moon Surgical CEO Anne Osdoit, and Chief Technology Officer David Noonan discussed the technology behind what they described as their system’s key benefit: the ability to collaborate with surgeons.

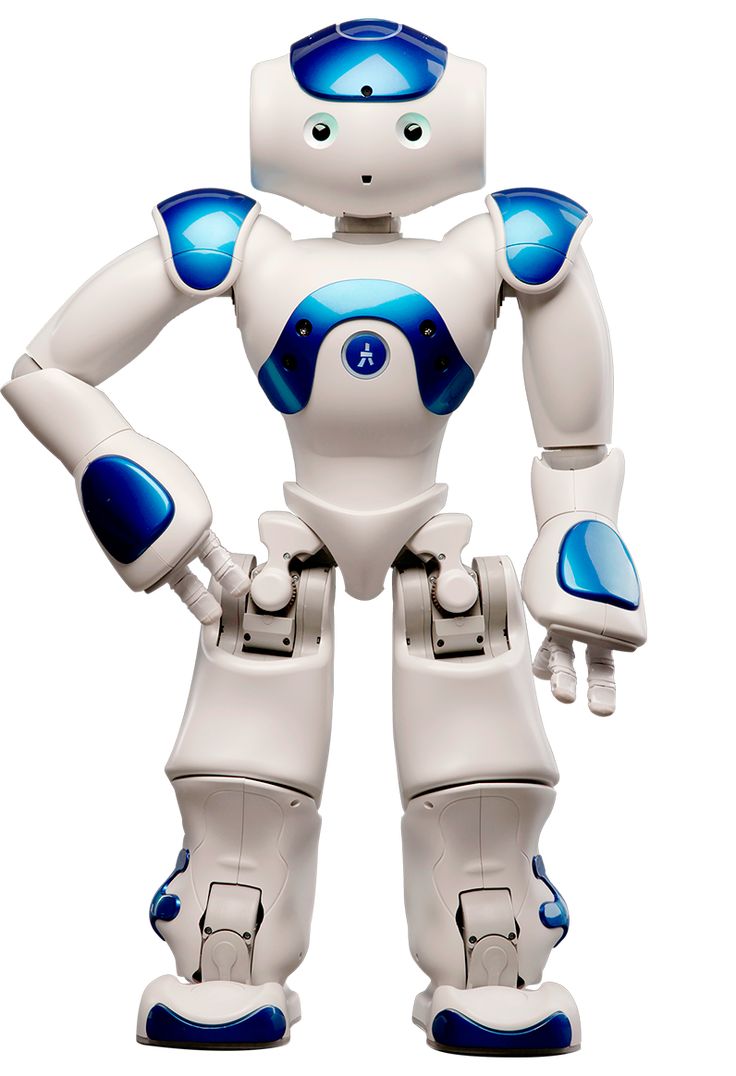

“We’ve built a collaborative robot, which is not necessarily what you typically see out there in the market,” Noonan said. “[Most] robot arms are extremely stiff. If you want to try and grab a hold of that and use it to manipulate it, you can’t because the payload and the stiffness are what’s needed to execute the task.”

But Maestro is designed to let surgeons directly move the laparoscopic instruments attached to its robotic arms and hold them in place. That reduces strain on surgeons and frees up assistants, increasing procedure efficiency and effectiveness.

“When a user attaches an instrument to our system, they still manipulate the instrument in the way that they used to before, via its handle if it’s a grasper or via the camera head if it’s a laparoscope,” Noonan said.

The technology convinced Dr. Fred Moll — co-founder of surgical robotics leader Intuitive Surgical — to join Moon Surgical first as an advisor and now as board chair.

Moon Surgical CEO Anne Osdoit. | Source: Moon Surgical

“His first reaction was somewhat skeptical, and until we really had something to show him and put into his hands, it was hard for him to picture what we would be doing,” Osdoit said. “That’s something we’re also experiencing with surgeons that we have to solve. Until they can touch and feel it, what we’re doing is so different from the other surgical robotic approaches that people have a hard time even understanding how it’s possible and representing it in their minds.”

Landing Moll is just one of Moon Surgical’s accomplishments this year. After winning its first FDA clearance for Maestro in December 2022, the device developer followed up with European Union CE mark approval in April 2023. Then came a $55.4 million funding round in May and the addition of Chief Financial Officer Anne Renevot and Commercial Strategy VP Lisa Jacobs to the leadership team.

Moon Surgical closed that Series B funding round less than a year after its $31.3 million Series A round — and about a year and a half sooner than Osdoit previously anticipated.

“Since we announced the A round we’ve had constant inbound interest from investors, and at the end of last year we realized there might be people out there willing to give us some money and in the current environment it would be foolish not to take it,” she said. “We had also reached a number of significant milestones that justified a new round with new pricing and new terms. Otherwise, I’m not sure our historical investors would have been supportive.”

The latest round will fund development and commercialization with a limited market release planned for 2024 and a full commercial launch in 2025.

Moon Surgical is improving Maestro’s design from the first version that won FDA and EU approval.

“It’s not a version of the device that we felt we could scale from,” Osdoit said. “We have basically translated all our learnings into a commercial embodiment that not only looks a lot nicer — it looks amazing — but has the same core architecture and functionalities and incorporates some of the learnings from our initial feasibility study where we’ve treated 50 patients.”

To scale for manufacturing, Moon Surgical is working to stabilize the design and assemble the necessary infrastructure and resources, particularly components for the arms that set Maestro apart.

Maestro’s light touch in the surgical robotics arms race

Moon Surgical’s Maestro surgical robotics system has two arms that can hold the same laparoscopic instruments that surgeons already use. | Source: Moon Surgical

Intuitive Surgical’s da Vinci system remains the leader to beat in soft tissue surgical robotics. But Osdoit thinks one reason surgical robotics hasn’t snatched a larger share of total procedure volume — besides the cost — is that surgeons aren’t comfortable operating on a patient from a surgical system console in the corner of the room.

“What we wanted to do when we started Moon was provide a solution that would deliver the benefits of robotic surgery — the things that surgeons love — maybe not with the complete degree of sophistication that you could have in a da Vinci system, but something that would be appropriate to cover the vast majority of surgical procedures, maybe even 70%, 80% of what you would do with the da Vinci,” she said.

Maestro’s disposable couplers allow surgeons to use the same laparoscopic tools as they did before, except they can do the same procedures with one fewer person in the room.

“The surgeon is his or her own assistant using our system,” Osdoit said. “The concept is it’s the robot that adapts to the surgeon and not the surgeon who adapts to the robots. For patients, we are hoping to increase throughput, reduce anesthesia time and give the surgeon better control and confidence over what’s done during the procedure, which ultimately should turn into better care for patients.”

To do that, Maestro allows surgeons to use their own hands to manipulate instruments but holds them perfectly still when the surgeon releases them.

“Our architecture is very different to that more traditional serial manipulator with stiff joints all the way along the degrees of freedom,” Noonan said. “Our design actually started as a haptic interface, in this case, an impedance control device which is mechanically transparent.”

While traditional robots are mechanically rigid, a surgeon can grab Maestro’s arms and move them around, with the robotic arms making themselves feel light by compensating for their own mass and the mass of the attached instrument.

And while a more traditional robot has a motor and a gearbox to provide torque amplification, Maestro’s system has no gearboxes.

“Our torque amplification comes from the combination of a capstan with a pre-tensioned tendon that wraps around and then goes to a larger capstan, so we get a gear ratio by taking a capstan wrapped around a smaller diameter pulley to a larger diameter pulley,” Noonan said. “And that approach allows you to basically amplify the torque while having very little backlash and no friction between gear teeth, which is what you get on a more traditional gearbox.”

The system senses motor current on the motor side to infer the force being applied to a joint, detecting when a surgeon is trying to move the arm in order to assist that movement.

“We’ve got multiple modes,” Noonan said. “The arm can act as a robot and it can move our laparoscope in order to track the surgeon’s tools to be able to reposition in a hands-free manner but also can guide the surgeon to a certain place, it can hold perfectly still, or provide feedback to the surgeon regarding what sort of force it’s experiencing elsewhere.”

The tendons are made of stainless steel, and the system also has a series of springs for passive compensation. While the bulk of the system’s weight is in its base, the team is trying to drive down the mass and inertia of the linkages and transmission mechanisms that extend to the distal joints.

Chief Technology Officer David Noonan. | Source: Moon Surgical

“You can algorithmically compensate for a lot of stuff, but there are some things you can’t,” Noonan said. “We’re trying to minimize that perceived mass because ultimately transparency of the system is really what we’re fighting for: it’s easy for the surgeon to move it, he or she doesn’t feel like it’s there, and it becomes the best possible assistant for that surgeon as opposed to a clunky or complicated tool they have to adapt to.”

What’s next for Moon Surgical

As Moon Surgical builds more Maestro systems, it will have to solve shortages of critical sensors like encoders.

“That’s been a real pain point,” Noonan said, with lead times of up to 40 weeks.

The Maestro system uses at least two encoders to measure joint angles at each motorized axis. All of the encoders are redundant, and the system compares the sensors on each joint to make sure each joint is working as needed — and that all the sensors are working as well.

“In surgical robotics, one of the things from a design perspective you’re always looking for is to make sure you never can have uncontrolled motion. That’s the big no-no,” Noonan said. “All our joints have redundant encoders, and you’re constantly looking to

detect a failure of one of those by constantly measuring the two of them.”

Moon Surgical is constantly scouring the internet for available encoders, and for early prototypes even resorted to buying products containing encoders solely for the encoders.

“In that case, you need to only have two of everything or, you know, 2X of everything. And then as we go through our verification and validation cycle and now we’ve got six units, we need to make sure you’ve got 6X of everything,” Noonan said. “As we go toward commercialization and what the build plan is for next year, you’re actually often making decisions based on what’s available as opposed to what you might prefer.”

Moon Surgical is currently assembling just about everything in the Maestro system except for the arms, with plans for final testing of the arms in the next few months before internalizing manufacturing. The company’s arm supplier is based in France, so internalization of the arm is to be done there while the rest of the work is happening in San Carlos, California.

“Our overall strategy is to keep a relatively lean and efficient manufacturing team,” Osdoit said, “which means that as the sub-components of our system get really stable over time, we would be able to outsource them to OEM partners and then just keep the final assembly and testing in-house and leverage our infrastructure and team more and more to get more throughput. … We’re at the beginning.”